Remember that values questions have a “you” in them. The goal is to involve people in relating what they see on the screen to their own lives, not to analyze the filmmaker’s technique or to engage in intellectual criticism. Allow the conversation to flow along a values and feelings track.

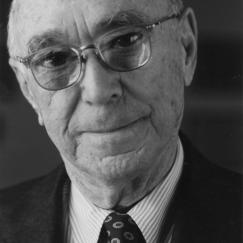

Bio/Short Description

Hailed as one of the scholars who helped overturn the dominance of behaviorism in the field of psychology with “the cognitive turn,” Jerome Bruner received his Ph.D. in psychology at Harvard in 1941. His mentor, Gordon Allport, had conducted groundbreaking studies of personality and had also explored the psychology of the new technology of radio (Cantril and Allport 1935). Bruner was interested in both experimental cognitive psychology and the field of cultural anthropology. But he hated the way both these fields seemed to decontextualize and devalue the role of place, setting, motives, and dispositions in the context of human cultural life (Mattingly, Lutkehaus, and Throop 2012).

In his research on child development, Bruner observed that perception is a creative process, not just a biological one, and that people respond differentially to various modes of representation for learning about the world: enactive representation (experience), iconic representation (images), and symbolic representation (language). Unlike Piaget, Bruner did not position these as a set of developmental stages; he recognized that symbolic thought does not replace the other modes as we engage with experience, images and language throughout our entire lifetime. But he emphasized that perception is also inextricably tied to particular cultural and social conditions of lived experience.

In a very real sense, Bruner believed that the way we see the world is shaped by our culture’s symbols. Not surprisingly, when Bruner first encountered the groundbreaking work of Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky, he was entranced (Bruner 1973). Vygotsky had explored the role of cultural context in human development in the 1920s and written his seminal work, Thought and Language, in 1932, working with A. R. Luria and others to create a new approach to psychology. But in Stalinist Russia, these works were immediately suppressed. For twenty years after his death in 1934, it was forbidden to discuss or reprint Vygotsky’s writing, and his work could be read only in a single central library in Moscow by special permission of the secret police (Dolya and Palmer 2005). After Stalin’s death, the works were circulated to the West, and Jerome Bruner wrote the introduction to the English translation of Thought and Language in 1962. This and another work of Vygotsky’s, Mind in Society (1978) had a substantial influence in the fields of both psychology and education (Cole 2009).

HOW THEY INFLUENCED YOU?

External Links

Other Grandparents

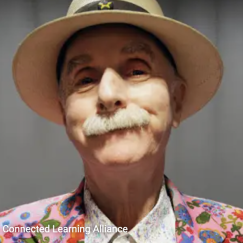

ColinPosted By: Renee HobbsOn:07/13/2025 - 00:50

ColinPosted By: Renee HobbsOn:07/13/2025 - 00:50

BillPosted By: Renee HobbsOn:06/29/2025 - 20:45

BillPosted By: Renee HobbsOn:06/29/2025 - 20:45

HowardPosted By: Renee HobbsOn:01/27/2024 - 22:47

HowardPosted By: Renee HobbsOn:01/27/2024 - 22:47

Gary Posted By: Renee HobbsOn:01/01/2024 - 00:39

Gary Posted By: Renee HobbsOn:01/01/2024 - 00:39

Clyde Posted By: Renee HobbsOn:04/04/2023 - 18:16

Clyde Posted By: Renee HobbsOn:04/04/2023 - 18:16

Hacer Dolanbay

Bruner, is very important in terms of media education. Because he has introduced cognitive learning to the world of education. It is not enough to learn competencies and skills to improve media literacy. People get a lot personal, community- social and cultural benefit from making sensible choices about information, using self-expression and using digital tools to join online share our interest and concerns around the world. I learned many thing from Bruner. During my university years I learned his structural, discovery learning model. This model involves students using their brains in a conscious way by exploring. This model is directly related to media literacy. We want people to be conscious and critical thinkers when exposed to the media. While they watching or reading to the media we want to they ask some questions to their media tools or context. Besides we want they create a new product about media or real life. These are learning by experienced and learning by live. I was impressed and in my media literacy class, I tried the discover by learning of my students.

Renee Hobbs

I encountered the work of Jerome Bruner through my experience at Harvard Graduate School of Education, where Howard Gardner, David Perkins and colleagues at Project Zero were exploring the relationship between mind and culture through looking closely at learning in the arts. Only after I had read his work did I realize how much his ideas had infiltrated by thinking about learning, culture and media. As a child, my mother used Man: A Course of Study with her 6th grade students and I remember poring over the curriculum materials at home.

Bruner certainly validated the idea that one’s creative self could be connected to one’s identity as a researcher, teacher, and learner. Perhaps, however, I’ve known this forever: while I love to learn by reading, watching, and listening, I actually learn best by making and doing things. An important aspect of my personal and professional identity has always come through creative expression. As an undergraduate, I enjoyed serving as a reporter and editor for the Michigan Daily, the college newspaper. I love the forced concision of Twitter and appreciate how my creativity flourishes under constraints of time, resources and format.

I am at my happiest when designing websites and interactive media, making videos, writing curriculum, composing essays, making speeches, curating images for my PowerPoints, and using a combination of moving images, language, and sound to express my ideas. So much of my creativity is practiced through collaboration. Making media provides a structure for engaging with both people and ideas—it is through working with people to create media and learning experiences that I do my best thinking.

One fundamental value of media literacy education is expressed in the idea that by making media, we learn. Jerome Bruner identified the powerful interplay between working with people and materials (“hands-on”) and working with ideas (“minds-on”) as fundamental learning practices. In the 1960s, this approach was revolutionary and Bruner’s ideas were fueling the revolution. In my own teaching, I have discovered that many abstract principles and ideas become more engaging and accessible to learners when approached in an activity-based experience. By the way, this is just as true for graduate students as it is for young children (Hobbs 2015).

Creative authorship is fundamentally a learning process: as Bruner explained, artifact creation is an essential aspect of cognitive activity and cognitive growth. He appreciated that for many learners, it is vital to explain “in things, not words, understanding by doing something other than just talking” (Bruner 1996, 151). And not only do such creative works instantiate the learning process; they inspire those who participate in creating and sharing them and cultivate “pride, identity, and sense of continuity” (22).

Today, most media literacy educators insist on emphasizing the intersections that connect critical analysis to creative-media production (in print, visual, sound, and digital formats) as a core element of pedagogical value, reflecting a Brunerian line of inquiry in which learning is understood as a socially, culturally, and materially embodied process.